When the media lose evidence, they lose trust

On the occasion of Médias en Seine, held on 15 January in Paris at the Maison de la Radio, we take a critical look at the weak but converging signals observed in the media ecosystem. Based on recent figures on mistrust, credibility and the role of the media, we explore a central question: what happens when attention is still there, but evidence and trust are eroding? An analysis to understand why demonstration is now becoming a key issue, both for the media and for advertising.

Stéphane LE BRETON

1/16/20265 min read

…and why advertising is directly affected

For several years now, a vague unease has been spreading throughout the media ecosystem. It is not a sudden collapse or a spectacular crisis, but rather a slow, gradual, almost silent erosion: the erosion of trust.

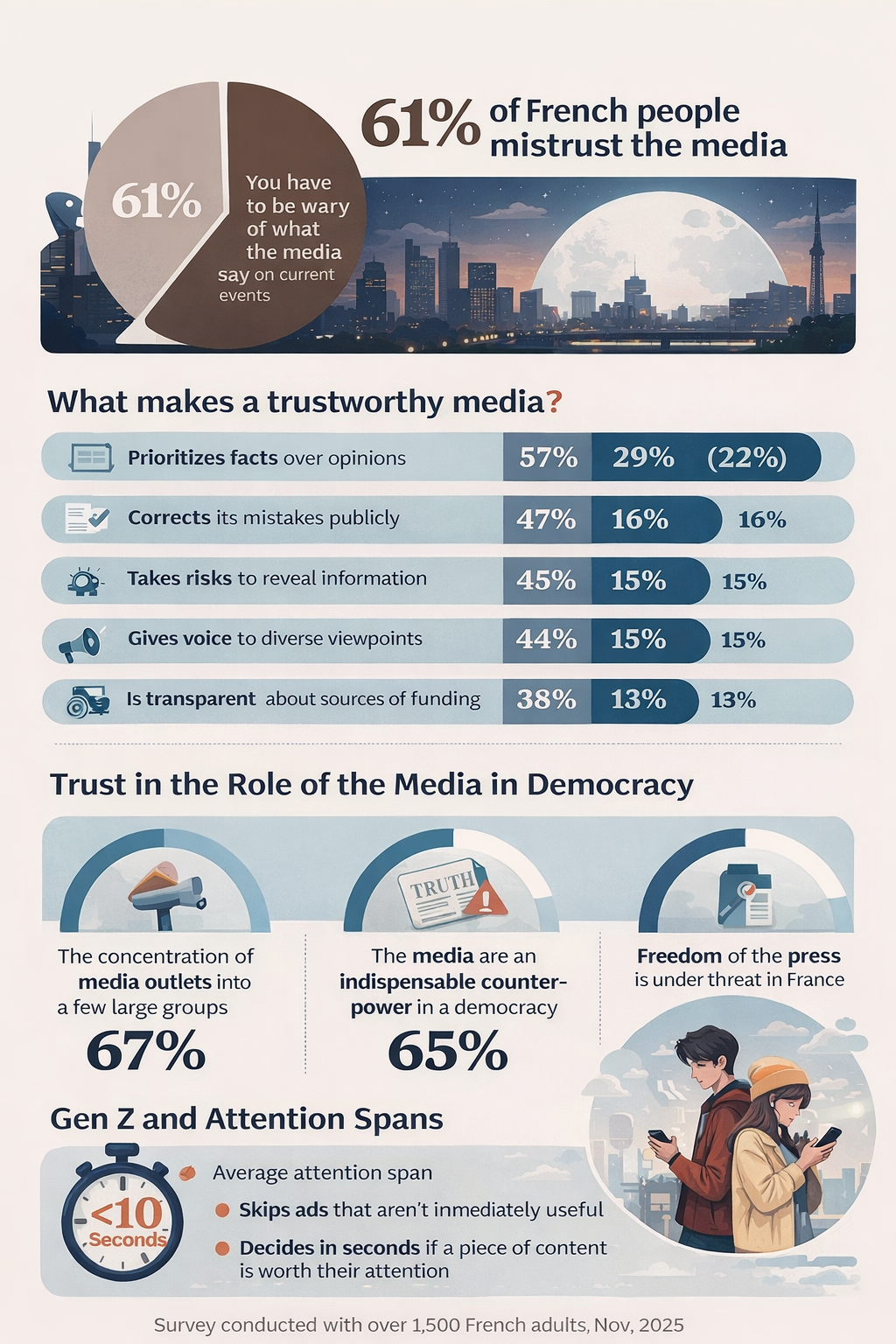

The figures published at the end of 2025 in the Media Trust Barometer are clear. They do not reflect a sudden shift, but rather confirm a fundamental trend.

61% of French people say they distrust the media.

A relative majority considers media group concentration to be a democratic problem. And, even more strikingly, the most frequently cited criteria for trust are neither reputation nor broadcasting power, but the ability to demonstrate.

This observation goes far beyond the field of information. It also — and perhaps above all — concerns advertising.

Distrust is not an opinion. It is a signal.

When we analyse the results in detail, one thing stands out: mistrust of the media is not ideological. It is functional.

The French do not say they reject information as such. They express a growing difficulty in placing their trust without proof.

The criteria that define a ‘trustworthy’ media outlet today are clear:

give priority to facts rather than opinions,

acknowledge and correct mistakes,

disclose sources and funding,

offer a variety of viewpoints.

In other words, trust is no longer based on status. It is based on demonstration.

This shift is fundamental. It marks the end of a historically vertical model, where authority was sufficient, and the beginning of a horizontal model, where credibility is built continuously.

When editorial trust erodes, advertising trust follows suit.

This point is rarely stated explicitly, but it is central. Advertising does not exist in a vacuum. It is part of a context of reception. When the credibility of a media outlet weakens, it is not only its editorial content that is called into question — it is also all of the messages it disseminates, including commercial ones.

This is not a criticism of the media. It is a well-documented cognitive mechanism: trust is transitive. An environment perceived as opaque, polarised or difficult to verify automatically weakens the reception of the advertising messages displayed in it. This phenomenon partly explains:

the decline in the incremental effectiveness of certain media investments,

the rise in advertising distrust,

and the increasing difficulty in creating lasting brand preference.

So the question is no longer just: ‘How many people have we reached?’

But: ‘In what climate of trust was this message received?’

Attention does not disappear. It becomes conditional.

Another key lesson emerges from recent debates — notably at Médias en Seine — and it deserves to be clarified: attention has not disappeared, even among the younger generations. But its nature has changed profoundly.

Despite the mistrust expressed towards the media, more than 70% of French people still say they follow the news with interest. This figure remains high, even if it has fallen slightly. It shows one essential thing: it is not disinterest that is growing, but the end of automatic trust.

This phenomenon is even more noticeable among younger audiences. According to several converging studies — Google/YouTube (Gen Z Decoded), Kantar Media Reactions, Deloitte Digital Media Trends — Gen Z does not have ‘less attention span’: it simply has much stricter acceptance thresholds. In practice, this means that:

The first few seconds are used to decide whether content is worth spending time on.

Any exposure perceived as useless, repetitive or not credible is immediately ignored.

The authority of the media or brand is no longer enough to justify the attention given.

Google's research shows that, for Gen Z, the first 5 to 10 seconds are decisive: not for understanding, but for assessing the value and credibility of a message. This point is often misinterpreted: it is not a lack of concentration, but a reflex for rapid sorting, forged in an environment saturated with content.

Less time allocated, more immediate demands

Kantar Media Reactions studies confirm this paradox: Gen Z is both the generation most exposed to messages... and the most critical of advertising. It rejects above all:

formats deemed too long,

messages perceived as “corporate” or self-declarative,

unsubstantiated promises.

Conversely, it values:

visible evidence

real-life experiences,

signs of authenticity and transparency.

In other words, the attention economy has become an economy of immediate credibility. It is not duration that is the problem. It is ‘unjustified’ time.

Research by TikTok Marketing Science shows that short formats (between 6 and 10 seconds) achieve the highest memorisation scores — provided that the message is perceived as sincere and credible from the very first seconds.

Brevity is therefore not an end in itself. It is a discipline.

The persistent misunderstanding about short formats

Many brands and media outlets continue to interpret this development as a constraint: ‘We have to make things shorter because people don't have time anymore.’ This is a simplistic interpretation.

The real constraint is not time. It is proof. A short message without credibility is ignored. A short message that conveys a clear signal of trust, on the other hand, can become a powerful trigger.

In this context, continuing to communicate as if repetition or authority were sufficient amounts to ignoring a profound change in habits — particularly among the generations that will shape tomorrow's audiences.

What this says about the future of media and advertising

We are entering a phase where:

Short formats are becoming dominant,

not because they are fashionable,

but because they are compatible with attention spans that have become more demanding.

Effective formats now share three common characteristics:

they respect the audience's time,

they spark interest without trying to convince immediately,

they open up a path for verification, rather than closing off the message

In a world where less than ten seconds can decide everything, the question is no longer: ‘How can I speak for longer?’ But rather: ‘How can I be credible more quickly?’

The case of social media and influencers: a false paradox

The figures are clear: social media and content creators are among the least trustworthy sources. And yet brands are investing heavily in them. Why?

Because these spaces offer something that traditional environments have sometimes lost: an illusion of proximity and verifiability.

It is not influence that creates trust. It is the ability to verify, to identify a voice, a face, a lived experience. When this proof is absent, mistrust reappears — sometimes even more violently.

The lesson is simple: trust does not come from audience size or format. It comes from the ability to connect a message to a real and relatable experience.

Media, brands, platforms: same fight, same challenges.

What these figures reveal is not the failure of the media. Nor that of advertising. Nor that of platforms.

This marks the end of a model based on credibility statements, in favour of a model based on contextualised evidence. In this new landscape:

Authority is no longer enough,

repetition no longer convinces,

short-term performance no longer compensates for the erosion of trust.

The players who will succeed will not be those who speak the loudest, but those who can demonstrate why their messages deserve to be believed.

Conclusion: trust can no longer be imposed

The figures from the Media Trust Barometer are not a passing warning. They are a structural signal, one that brands, media outlets and platforms can no longer ignore.

Trust can no longer be decreed. It must be demonstrated. And in a world saturated with messages, demonstration becomes the real competitive advantage.

Each row shows three values: the share of respondents who cite the criterion as their primary trust factor, those who consider it important but not decisive, and those who do not see it as a key element of media trust.

Our commitment

Reviving trust in brand advertising through innovation.

CONTACt

info@buytryshare.com

+33 6 83 53 70 41

© 2025. SLB consulting. All rights reserved.