Influence, Distrust and Proof: Why the Advertising Industry is Reaching a Tipping Point

Brands have long operated on a simple premise: a good story is enough to convince consumers. In 2025, this logic no longer holds true. Influencer marketing budgets are skyrocketing—72% of European brands plan to increase their investments in 2026—but trust is plummeting. Audiences are consuming more content than ever, but they are less and less likely to believe what they see. Influencer marketing is thriving. Credibility, on the other hand, is evaporating. This edition of AdTrust explores this paradox and demonstrates how certified proof (NF522 / ISO 20488) is becoming the new foundation of advertising effectiveness, far beyond influence. With BuyTryShare, this shift is finally taking operational shape.

Stéphane LE BRETON

11/29/20256 min read

The central paradox: social networks are used extensively... but are highly unreliable

Social media platforms have never played such a central role in Europeans' daily lives: according to GWI (2024), we now spend more than two hours a day on them. This massive presence might suggest fertile ground for commercial communication. But the data paints a very different picture.

According to the Edelman Trust Barometer (2024), less than a third of European citizens say they trust the content they encounter online. And recommendations from influencers, despite their ubiquity, convince less than 20% of consumers (Kantar, Media Reactions 2023).

This profound disconnect — high consumption but low confidence — is what analysts now refer to as the integrity gap: an environment where the abundance of signals contrasts with the fragility of their credibility.

A structural confidence deficit

This discrepancy is not the result of an isolated phenomenon but rather a combination of factors:

the proliferation of sponsored content;

insufficient transparency around commercial partnerships;

an erosion of perceived authenticity as creators professionalise their activity;

regular scandals related to fake followers, bots and artificial engagement;

and the increasing difficulty for users to distinguish between a sincere testimonial and a paid narrative.

In this context, influence suffers from a fundamental bias: as soon as content is remunerated, it is spontaneously interpreted as a form of advertising.

This interpretation is all the more valid given that, as Nielsen (Global Trust in Advertising) points out, sponsored messages disseminated by influencers are viewed with the same caution — or even mistrust — as traditional advertising messages.

In other words: The story of a paid influencer does not speak ‘as a peer’, but as an additional advertising medium. And audiences are no longer fooled by this.

Influence: real reach, limited credibility

It is no coincidence that influence continues to grow in marketing budgets (+72% in 2026 according to Kolsquare): it allows brands to quickly reach engaged communities, multiply touchpoints, and embody brand messages with proximity.

But behind this dynamic, one thing is clear: influence has undeniable reach, but limited credibility. The data is unequivocal.

Low, documented and persistent confidence

According to Nielsen Global Trust in Advertising,

Only 33% of consumers trust recommendations from influencers,

while 70% trust consumer reviews, even anonymous ones.

Kantar's Media Reactions study (2023) points in the same direction:

Influencer content ranks among the least credible commercial formats,

just above digital banners... and far behind certified reviews or word of mouth.

At European level, the EU Digital Services Consumer Survey (2024) states:

63% of respondents believe that influencers ‘say what the brand wants to hear’,

and 57% perceive their sponsored content as ‘disguised advertising’.

In other words: Influence speaks loudly, but it no longer convinces as easily.

a. Trust automatically falls with remuneration

Harvard Business Review (2023) demonstrated a simple but essential phenomenon: when consumers know that a creator is being paid, perceived trust drops by an average of 18%. This loss of credibility is not marginal: it is structural.

The more a designer is recognised as a ‘professional’,

the more his activity is perceived as a business,

the more his independence of judgement is called into question.

Influence is therefore caught in an operational paradox:

Amateur creators are perceived as credible but lack reach,

professional creators have reach but lack credibility.

b. An audience that consumes... but no longer believes

The GWI 2024 report shows that:

76% of influencer interactions come from 16–34 year olds,

but 64% of this population believe that influencers ‘are too commercial’,

and 52% say they ignore sponsored content ‘on principle’.

It is not a lack of interest in the influencer. It is a cognitive mechanism of self-protection against excessive commercial solicitation. The audience scrolls, watches, enjoys, but no longer believes.

c. Influence = publicity: an equation perceived as obvious

The very nature of the creators' business model requires a form of narrative alignment with the brand:

well-defined content,

approved messages,

consistent storytelling,

carefully crafted presentation.

From a consumer perspective, this brings the influencer closer to the brand itself. That is why, as Nielsen points out, sponsored content posted by creators is no longer interpreted as testimonials, but as extensions of advertising: an additional channel, a paid vehicle. In any case, not a credible peer.

This is not a criticism of the profession but a perceptive reality — deeply rooted and measured.

d. What this means for brands

All the data points to influence:

generates visibility,

stimulates engagement,

fuels consideration,

but is not a sign of trust.

Influence remains relevant for informing, entertaining or activating... But its role in reassurance, proof and credibility has become marginal. One conclusion emerges: Influence is not in a crisis of audience — it is in a crisis of trust.

And at a time when consumers are demanding authentic and audited signals, this distinction is becoming central to advertising effectiveness.

Civil evidence: a new currency of trust in a market saturated with promises

While influence has profoundly transformed the way brands communicate, it has not resolved the central issue: trust.

However, data shows that this is no longer being rebuilt using traditional channels (advertisements, creators, sponsored content), but rather using a different type of signal: the verified experience of real customers, expressed in the form of certified reviews.

In a market saturated with messages — between 2,000 and 15,000 per day according to Yankelovich Research and Forbes — evidence has become a rare resource and the primary factor in persuasion.

1. Certified reviews: a signal perceived as inherently reliable

All studies agree: consumers overwhelmingly trust the opinions of other buyers, even strangers. Some key data:

BrightLocal 2024 :

49% trust online reviews as much as they trust the opinions of friends and family.

70% read between 5 and 10 reviews before making a purchase.

‘Authenticated’ reviews — clearly identified as verified — increase conversions by 18 to 28%.

Nielsen Global Trust in Advertising :

Consumer reviews (even anonymous ones) are the number one format in terms of trust, ahead of word of mouth and far ahead of advertising (22%) and influencers (33%).

Bazaarvoice / Northwestern University :

Adding a moderate negative review — known as the ‘imperfection paradox’ — increases overall credibility by 25%.

Products with at least five verified reviews see their conversion rate increase by 21%.

Experienced evidence is more persuasive than the best narrative.

2. Why are certified reviews more reassuring than advertising or influencers?

Three fundamental reasons emerge from European studies:

a. Indépendance perçue

A review is submitted by a customer with no contractual relationship.

This customer feedback does not follow a script.

This opinion reflects actual usage, not an editorial line.

b. Confirmation bias

Advertising exposes when reviews are valid or invalid. Consumers use reviews as a verification filter: ‘Is what the brand promises confirmed by others?’

c. Risk reduction effect

The more the choice involves cost, commitment or risk of error, the more opinions become decisive — particularly in:

automobiles,

household appliances,

insurance,

tourism,

telephony/internet.

Evidence helps to avoid post-purchase regret, which behavioural psychology refers to as the risk-mitigation effect.

3. Certification as a key element: NF522 and ISO 20488

The effectiveness of reviews depends on their perceived reliability. This is where standards come in.

NF522 / ISO 20488: the trust framework. These standards guarantee that:

reviews come from authenticated customers,

each review is verified,

no reviews are purchased,

no reviews are deleted for commercial reasons,

moderation follows a transparent protocol,

all data is traceable and audited.

This level of rigour transforms the opinion into a reliable, enforceable, comparable and actionable signal in marketing strategies.

This is the major difference between structured evidence and spontaneous opinion.

4. The evidence covers all stages of the buying cycle

The work carried out by Stars & Stories/BuyTryShare has demonstrated that certified reviews influence all four stages of the purchasing journey:

First, Awareness

Reviews increase visibility in search engines via rich snippets.

→ +7% to +30% clicks according to BrightLocal.

Then comes Comparison (Consideration)

Consumers use reviews as their number one criterion for deciding between similar products.

→ Decisive in food, cosmetics and electronics.

Next is the Purchase (Decision)

Certified reviews increase conversion rates by 18% to 28%.

→ Particularly strong effect on high baskets

Finally, there is the post-purchase evaluation (Evaluation).

Reviews fuel the cycle of trust.

→ 47% of shoppers say they are willing to leave a review (Stars & Stories, 2024)

Evidence no longer serves to validate the end of the process: it structures the entire cycle.

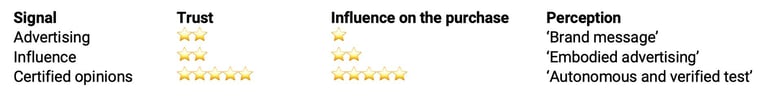

5. Why does evidence trump influence?

By cross-referencing all the data (Nielsen, BrightLocal, Northwestern, BuyTryShare), a clear pattern emerges:

The conclusion is clear: influence entertains. The evidence is convincing.

Conclusion: An industry that can no longer ignore the evidence

The transformations observed in these lines all follow the same trajectory.

On the one hand, influencer platforms are attracting increasing attention — but trust in them is eroding.

Advertising overload, creator remuneration and content scripting now limit the real impact of recommendations: they sometimes inform, they often entertain... but they no longer convince.

On the other hand, consumers are shifting their trust towards signals that are perceived as independent, authentic and verifiable: certified reviews.

They are becoming the new grammar of credibility: a language where proof takes precedence over promises, where lived experience takes precedence over storytelling, where peer validation takes precedence over staging.

This development is not insignificant: it overturns the hierarchy of signals that influence purchasing decisions.

In this context, brands wishing to restore trust can no longer rely solely on creativity, influence or repetition. They must incorporate an essential element into their strategies: proof, in the strict, structured and certified sense (NF522 / ISO 20488).

It is precisely this shift — from discourse to evidence — that opens up a new field of opportunities for the advertising ecosystem.

Only when a brand is able to show what its customers are really experiencing does it regain that fundamental lever that audiences have been demanding for years: trust.

Our commitment

Reviving trust in brand advertising through innovation.

CONTACt

info@buytryshare.com

+33 6 83 53 70 41

© 2025. SLB consulting. All rights reserved.